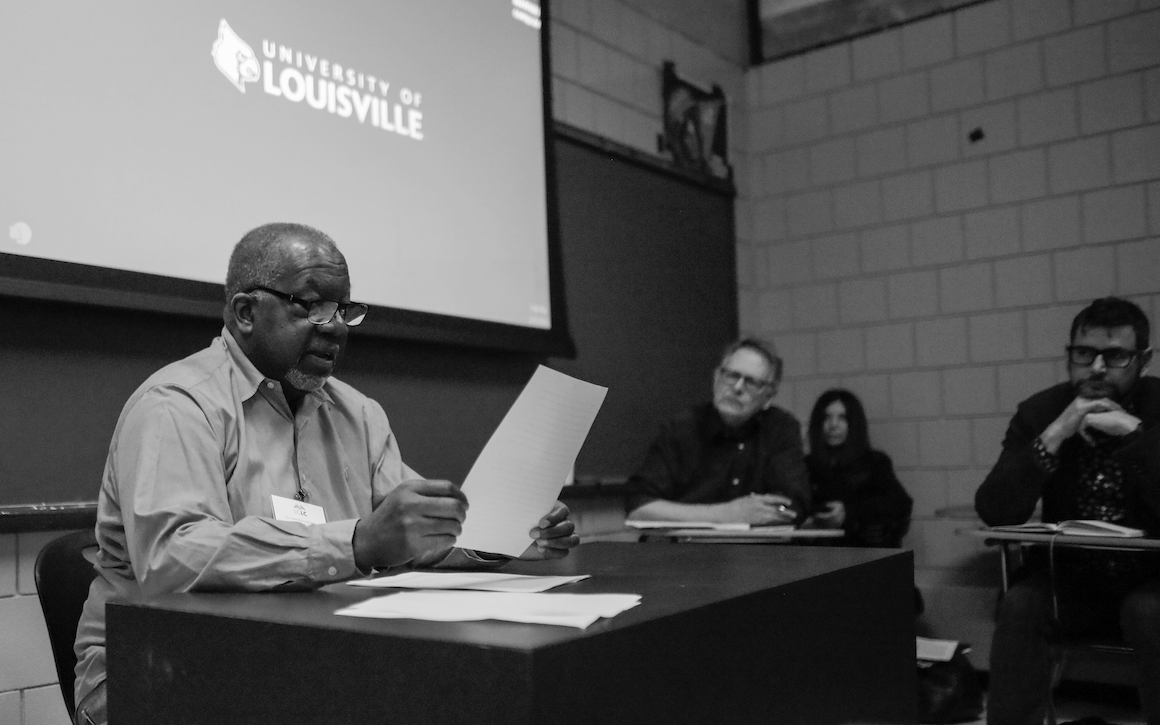

Photo by Aldon Nielsen

Tyrone Williams’ death earlier this month came as a shock to his innumerable friends in the poetry community and beyond. Tyrone was my colleague at Xavier University for forty years, and one of my closest friends. We both taught courses in poetry, in literary theory, and in modern American literature. As we begin to come to terms with his loss, and move more deeply into his extraordinary body of work in both poetry and criticism, I am delighted to publish this late paper on Langston Hughes, originally given at the Louisville Conference on Literature and Culture in 2023, at a panel organized by Barrett Watten. I am indebted to Barrett, who offered me the paper, and who provides an introduction below.

—Norman Finkelstein

Note on the publication of “Bessie, bop or Bach”: Iconoclasm—and Not—in Montage of a Dream Deferred”

As poet/critics inspired to experiment in both creative and critical writing, Tyrone Williams and I shared a M.O., modus operandi or method of operation, in common. We both use the academic conference as a time-and-space-specific medium for developing and road-testing ideas in poetics and literary theory. Over the years Tyrone and I collaborated on a number of sessions that advanced ideas in a fluid discourse in the creative commons of poetics—as he has done with many others, notably Aldon Nielsen and Lauri Scheyer. There was that memorable session at the 2012 Modernist Studies Association in Las Vegas on “Learning from Detroit,” where Tyrone presented an original paper titled “Detroit Closures: After Fordism and Gordyism,” bridging the economics of Fordism with Motown’s cultural assembly of the “good life” in the 1960s. In 2017, again at MSA, I asked Tyrone, along with Herman Rapaport, to join a discussion on “Transvaluations of Value: Poetics & Political Economy.” Tyrone’s produced an act of critical transvaluation in his essay, “’The Changing Same’: Value in Marx and Amiri Baraka”—which was immediately snatched up and published in Ruth Jennison’s edited volume Communism and Poetry: Writing Against Capital (Palgrave, 2019), taking its place with the heroes of value critique of our time. Tyrone was comfortable in Left and poetics discourses, equally. For the Louisville Conference in 2023, I wanted to return to the question of value, as much economic as literary, in a session titled “Transvaluations of Value: Poetics & Political Economy,” soliciting contributions by Tyrone, Adeena Karasick, David Kellogg, and me. Tyrone’s reading of Montage of a Dream Deferred was breath-taking, his delivery captured by the conference photographer and posted online. While I had hoped to find a timely publication of the set of papers as a whole, only my essay, “Questions of Value: Poetics as Living Labor and the Specter of Past Work,” has appeared (in Lana Turner 16). I am therefore delighted that Restless Messengers is making this exemplary piece available as a tribute to Tyrone’s work, in good time. And I hope, as well, that Tyrone’s critical oeuvre, parallel to his many experiments in poetics, will begin an overdue process of assembly, truly a unique contribution whose rigor and responsiveness combine in a moment’s notice.

—Barrett Watten

“Bessie, bop or Bach”: Iconoclasm—and Not—in Montage of a Dream Deferred

by Tyrone Williams

Montage of a Dream Deferred has been celebrated as not only one of Langston Hughes’ great poems but also one of the great poems of the American mid-20th century. It features Hughes’ typical quotidian subject matter, the everyday speech patterns and diverse lexicons of Harlemites in the wake of the Harlem Renaissance, which is to say, during the Great Depression and postwar period. Intermixed with, indeed, as part of, the quotidian are political, social and cultural commentaries that belong to a voice only less common than that of the “ordinary” Harlemite, a voice that echoes the sentiments of Hughes in his other poems, even if we cannot assume that several, or even a few, of the voices registered in Montage “belong” to Hughes.[1] For example, in the dramatic polylogue[2] of Montage, the list of dreams of the speakers culminate with this desire and observation: “I'd like to take up Bach. / Montage/ of a dream/ deferred. / Buddy, have you heard?” What interests me is not only the kind of code-switching or polyvocal structure that occurs throughout the poem, signaled here by the unusual but appropriate word “montage,” but also the link drawn between a postponed dream and the European composer J.S. Bach. There are, of course, many postponed and destroyed dreams scattered throughout the lyrics that comprise the serial poem, as many dreams, one might say, as there are voices. So this particular voice’s dream, taking up Bach, cannot be read as strictly autobiographical or generally “typical” of Harlemite musicians (not even casual, if trained, pianists), even if the poem erases the boundary between autobiography and biography by emphasizing that a voice like Hughes—educated, literary, etc.—is merely one among many other literate, educated, Harlemites. At the same time, this voice, this dream, appears at least three times throughout Montage, suggesting that the desire to take up Bach might well have been a common enough ambition among a certain sector of Harlem musicians, trained or not. In other words, it is difficult to decide if this vocalized desire belongs solely to Hughes, to someone like Hughes, or to a small but notable sector of Harlem musicians and so, unlike Hughes. Just as a melodic passage or chord pattern signifies a specific “character” in opera and musicals, so too the repetition of “Bach” in different contexts suggests a specific “voice,” “character” or “type” in Montage. However, it may well be the case that the three references to Bach “characterize” at least three different characters who all aspire to “take up” Bach. In short, even if we are tempted to say that one of these voices sounds like, or is in fact that of Hughes, himself a resident of Harlem, we cannot say that all three are variations on his voice without risking misrepresenting this poem’s ensemble of singular and multiple narrators.[3]

With these qualifications and uncertainties in mind, we might still venture to understand the invocations of Bach on several levels. In a poem whose rhythms are influenced by, and whose references are often directly related to, the old blues (Southern) and the new jazz (bebop), bypassing the over-commodified swing music of the Twenties and Thirties, the references to Bach underline the musical skills and competency of any blues or jazz musician, professional or not, capable of, and here, interested in, taking up one of the pillars of European classical music. From a listener’s perspective, Bach functions as a metonym for one of several types or genres of music one might enjoy. For example, Bach records appear as the last in a list of possible Christmas presents in one of Hughes’s most well-known poems, “Theme for English B”: “I like a pipe for a Christmas present, / or records—Bessie, bop, or Bach.” (24) The disjunctive “or” might reflect the narrator’s awareness of the limited funds available to the person from whom he expects a Christmas present. Beyond the specific context of “Theme for English B,” the Bach references might also underscore the defensive anxiety that afflicted some jazz musicians and critics, the belief that, given the assaults against the genre by American and European critics, the music had to be defended by way of comparative musicology, that it was just as complex and aesthetically noteworthy as European classical music. In general, though, Hughes is less apologetic than defiant when it comes to what the new jazz signifies: “Letting midnight / out on bail / pop-a-da / having been / detained in jail / oop-pop-a-da / for sprinkling salt / on a dreamer's tail / pop-a-da” (“Jam Session,” 22) Still, Hughes is not indifferent to the pathos that also attends this defiance: “Way up in the treble / The tingle of a / tear. / Be-Bach!” (“Lady’s Boogie”) The pun on tear—to cry, to rent (perhaps also a sign of the effort needed to reach “Way up in the treble”)—is reflected in the pun that simultaneously captures a critic’s imperative and a jazz player’s torqued retort, refusing to “be” Bach by bopping Bach. Finally, Hughes might also be mocking the black bourgeoisie who, per E. Franklin Frazier, often mimicked the high falutin’ ways of the white upper classes by ostentatiously displaying a taste for European classical music and fine cars: “Now you've got your Cadillac, / you done forgot that you are black. / How can you forget me / When I'm you? // But you do. (“Low to High,” 25)

Yet, pace Frazier, it would be too easy to simply accept the racialization of class structures as a self-evident truth. Doing so would imply that many, if not all, of the dreamers that populate Montage are merely bourgie wannabes, that their aspirations for more material goods, more economic security and its “proofs,” like taking up Bach or purchasing Cadillacs, merely confirm their susceptibility to acculturation. Untangling the sundry desires for economic and material security, for middle-class status, and for the skin tone, hair textures and speech patterns of white people is one of the consequences of the structure of Montage. Moreover, while labor under capitalism is occasionally criticized in Montage, not only from Hughes’s semi-Marxist perspective but also from the ordinary perspective of people who don’t “believe” in work, no matter its material, character-building or other “rewards,” the character complaining in “Necessity” might not represent Frazier’s ideal class-conscious revolutionary: “Work? / I don’t have to work. / I don’t have to do nothing / but eat, drink, stay black, and die.” The fact that the speaker eventually realizes that he or she “does / have to work after all” only supports the poem’s title: individual stoicism is what counts here, not any kind of philosophical or theological comment on labor as the wresting of culture from nature.

Thus, if black middle class aspirations only overlap with, but do not map exactly onto, white middle class values, the larger question of American racial relations in the postwar period is still pertinent to the various speakers that comprise Montage. We come across poems that envision a culturally pluralistic future (“Projection”) even as others offer a pessimistic assessment of reconciling the divergent values underpinning American multiculturalism (“Mellow”). At the same time, embracing cultural productions and values beyond those of one’s race or ethnicity pits iconoclastic desire against the solidarity that ethnic and racial minorities often presuppose. The resulting tension is reflected in poems that celebrate the various facets of Harlem life without moral or political judgment, as opposed to other poems which decry the limited social, economic and cultural opportunities for African Americans. Why call this relationship tense when it apparently seems so causal, that the reason the denizens of Harlem shouldn’t be judged is because of the narrow scope of social, economic and political opportunities available to them? Since the overriding theme is indefinite deferral of those opportunities, it would appear that the ethos of those living in what some scholars have deemed the “dark ghetto” is less a placeholder for a more robust set of moral and ethical principles congruent with the removal of “artificial” barriers to development and growth, than the permanent congealing of values necessary for survival in an unremittingly hostile environment.[4] This tension, which comes down to the old nature/nurture debate, has never abated as racial boundaries have alternately softened and hardened among black and white Americans during the seventy-plus years since Montage was first published.[5]

So what of those black dreamers light enough in skin tone, with straight enough hair texture, to pass for white, those whose dreams have apparently arrived in, if not necessarily on, time? In “Passing” Hughes considers these individuals and the lives they have chosen to live on the other side. The poem is, like several of the longer lyrics that comprise Montage, one enjambed sentence, broken up into clauses, suggesting a continuity or linkage across boundaries. The poem’s focus is not on “downtown” in lower Manhattan but on a “sunny summer Sunday afternoon in Harlem.” Nevertheless, “downtown” still interferes with life in Harlem as “grandma cannot get her gospel hymns / from the Saints of God in Christ / on account of the Dodgers on the radio.” Though those who disappeared into white society “miss” Sundays in Harlem “when the kids look all new / and far too clean to stay that way,” the trespassers may still perform a service to the black community since their very existence, never mind their undercover forays unto the enemy’s strongholds, disrupt the narrative of racial purity, a narrative which, having no access to, much less knowledge of, “invisible” genes, had to rely on visible tell-tale signs. Still, the note of regret Hughes wants to emphasize here echoes the dominant strain of melancholy in the protagonists of passing novels like The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man, Passing, and Black No More. And since the poem ends with the pyrrhic victory of having dreams come true, Hughes implies that the deferred dreams of those too dark or proud to disappear into white society might well be the lucky ones.

Still, insofar as class and racial passing, like the indeterminacy of voices throughout the serial poem, renders American society a kind of montage per se,[6] we might consider the value of this technique for Hughes. As critics have noted, montage is not only a cinematic technique, formalized most notably in the films and essays of Sergei Eisenstein, but also a photographic technique. Moreover, the origin of montage can be traced back to the Cubist work of Braque and Picasso, itself influenced by African art. I trace this lineage in order to suggest that montage, for Hughes, not only recuperates its African roots but also insists on its African American modernist contemporaneity in the vocal rhythms and speech patterns of ordinary Harlemites. And these patterns and rhythms are only two of the multiple sources of bebop.

Still, European classical music, for which Bach is a synecdoche, has its own relatively autonomous history. In Hughes’ United States, this history can be claimed as part of the heritage of black Americans insofar as Bach can be found, however transmuted, in jazz. The desire to listen to (on “records”) and learn how to play (“take up”) untransmuted Bach, Bach per se, to go back to Bach, to appreciate Bach vis-a-vis jazz (which, for some, means that Bach appreciates in value in relation to jazz), is not unlike the desire to have a newfound appreciation for African art vis-à-vis Cubism and its child, montage. And though appreciation, in both its aesthetic and financial senses, was still “available” to many Harlemites in the 1940s, there is no doubt that the landscape, as real estate, which had long been shifting beneath their collective feet, was on the verge of collapse. In one sense, then, appreciation for the culture of the “other” can be understood as another form of passing for the sake of personal survival. In another sense, however, appreciation can be read as an aggressive annexation of the culture of the other. And as we know, the payoff of appreciation differs according to class and race regardless of individual or collective intentions. For the speakers in Hughes’s Montage, appreciation is irreducible to compensation for the economic, social and political obstacles raised by Jim Crow. It is a form of intellectual and aesthetic development, self-edification per se, whatever its social and cultural ramifications. And the slip of the noose is precisely the indeterminacy of those ramifications.

But what happens when the noose becomes the predestined fate of so many it settles into the landscape as a permanent feature? What happens when a black person or persons taking up Bach does so at the risk of having to pass for black? This phenomenon was yet a few years in the future of Hughes. For us, however, living in a time when talking white is a perfectly comprehensible phrase, Hughes’ “Bessie, bop or Bach” may sound like child play, the dribbling alliteratives of a baby. It may be hard for us to believe in a time when ordinary Harlemites, hearing that phrase roll off the tongue, would have nodded, appreciating the sentiment. For they would have understood, as Hughes and so many extraordinary Harlemites did, that culture is the underground railroad by which the Jim Crow laws, de facto and de jure, might be sub-navigated, because cultural products can sometimes go where human bodies cannot. Yes, possessing products like a Bach record can sometimes be as consequential as walking into “enemy” territory. Of course, social excommunication is not as dangerous as the threat of lynching, but in tight-knit communities in which uniformity of beliefs and values is paramount, a cosmopolitan taste in cultural products may be tantamount to sleeping with the enemy.

Tyrone Williams (Feb. 24, 1954—March 11, 2024) was a poet, critic, and professor. Born in Detroit and educated at Wayne State University, he taught at Xavier University from 1983 to 2023, when he retired to assume the position of David Gray Chair of Poetry and Letters at the University of Buffalo. His areas of teaching expertise included Modern and Postmodern American Literature, African-American Literature, and literary theory. The author of eight full-length volumes of poetry and numerous critical articles and reviews, he traveled extensively, giving poetry readings at venues across the country, as well as critical papers at many academic conferences. An active figure in the national poetry community, judging prizes and editing various publications, he was beloved and admired by his contemporaries, and served as a mentor to many younger poets.

Photo by Photo by William Dickson, Jr.

[1] Nor can we presume that Hughes has only one voice. Is the Hughes of “Theme for English B” the “same” Hughes that keeps intoning a “dream deferred” throughout Montage?

[2] Although the shift between italicized and regular fonts might suggest two speakers, and this a dialogue, the various things desired seem to belong to several speakers.

[3] This dilemma raises the more general question of the number of characters in the poem. As with the references to Bach, are there other repeated images and ideas that “belong” to the same character? Or are we to understand that the same dreams belong to many separate characters?

[4] This is, in essence, one of the major themes of Tommie Shelby’s book The Dark Ghettos: Injustice, Dissent and Reform.

[5] The most recent issue of Chicago Quarterly Review, edited by writer Charles Johnson, offers both a sense of the limits and opportunities available to 21st century African Americans, suggesting that Hughes’s “Bessie, bop or Bach” is, today, less the taste of a multicultural iconoclast than it is a metonym for the hardening walls between white and black Americans.

[6] That is, a collage that is spatial and temporal, regional and historical, its components as audible (in speech patterns and dialects) as visual, confounding not only racial but also, often, ethnic categories.