Atlantis, an Autoanthropology:

A Restless Messengers Symposium

Duke University Press, 2022, $24.95

A Restless Messengers Symposium

Nathaniel Tarn, Atlantis, an Autoanthropology

Duke University Press, 2022, $24.95

Rachel Blau DuPlessis

Elizabeth T. Gray, Jr.

Joshua Hoeynck

Rachel Kaufman

Jed Rasula

Mark Scroggins

It is my great pleasure to devote this second Restless Messengers symposium to Atlantis, an Autoanthropology, by Nathaniel Tarn. Born in 1928, Tarn, poet, anthropologist, translator, editor, and world traveler, now gives us a work of brilliant originality, simultaneously a memoir, an ethnography, a sweeping masterpiece of travel literature, and above all, a poetic testimony of unflinching intelligence and grand passion. Written over the courses of many years, the thirty-three “Throws” of Atlantis, each a venturing chapter in the life and thought of this essential writer, take us across the globe and deep into Tarn’s heart and mind. Beginning with an Introduction by Peter O’Leary, seven poets and critics have gladly written responses to this remarkable book. Their thoughtful engagement with various aspects of the text indicates what an important contribution it is to our understanding of poetry and culture in our time.

—Norman Finkelstein

Introduction

Peter O’Leary

Peter O’Leary

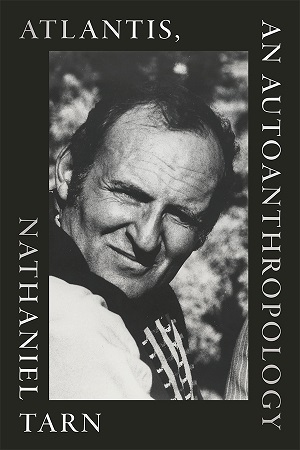

About William Morris, Yeats wrote, “If some angel offered me the choice, I would choose to live his life, poetry and all, rather than my own or any other man’s.” I used this quotation a decade ago on May 1, 2012 when introducing Tarn for the lecture he gave in the History and Forms of Lyric series at the University of Chicago, the first time in over a half century that he had returned, in any formal sense, to his alma mater. (His lecture, entitled “On Poetic Production, the Embattled Lyric and a Topography of Hope,” and published in Hambone 20 (Fall 2012), is well worth tracking down.) The publication of Atlantis, An Autoanthropology justifies the Yeats quotation emphatically. What a life! The photographs alone are alluring—Tarn as seen by Henri Cartier-Bresson; Tarn and Paz; Tarn’s iconic photo of Duncan. The episodic, serialized depictions of the life and thought, in the form of the repeated Throws (Tarn takes the notion of these throws from ceramics) are as lyrical as they are beguiling.

Pound’s list in “How to Read” of “clearly definable sorts of people” who go about charging language with meaning “to the utmost possible degree” includes four kinds of poets—inventors, masters, diluters, and writers of mostly good work in the more or less good style of the period—followed by two seemingly more peripheral contributors—writers of belles lettres and “starters of crazes.” Now, poetically, Tarn is a master, specifically a master of the New American Poetry, and in particular, one of the great elegiacal poets writing in English, among whose many highlights must be mentioned The Persephones, Lyrics for the Bride of God, The House of Leaves, Alashka, Seeing America First, as well as the three utterly remarkable late-in-life volumes from New Directions, The Ins and Outs of the Forest Rivers, Gondwana, and The Hölderliniae, this last only published last year, an absolute masterpiece (and vividly reviewed by our host, Norman Finkelstein). But I mention Pound’s list to underscore the importance of memoir and belles lettres when it comes to charging language with meaning to the utmost possible degree. Memoirs and correspondence have played an outsized role in my education as a poet, tantalizing an unquenchable desire for the feel of any given time and place as a way of entering into the poetry, even a time and place I’ve lived through and in. (I would add that to a secondary degree, biographies of poets have been similarly vital.) With Atlantis, Tarn defines his era, becoming its poetic embodiment, prophet of the lost continent of poetry, wish, and imagination that is always receding into our poetic dreams. Atlantis will surely take its place alongside Duncan’s H.D. Book as one of the crucial poetic documents of the second half of the twentieth century, while then also creeping, as it does, thanks to a very long life, into the twenty-first, setting a standard for this century.

Rather than rehearse the strengths and powers of this remarkable book, I want to focus my remarks here to two portions of its contents. The first is Tarn’s involvement with publisher Jonathan Cape in 1967, which led to the formation of Cape Goliard Press, which published books by Charles Olson, Allen Ginsberg, Jonathan Williams, and Zukofsky’s Catullus translations, among others, and the formation of Cape Editions, for which Tarn was the series editor, issuing works of New American poets, European poets in translation (especially Eastern European poets), critical theory, anthropology, and political science published in uniform editions (same size, same typography) in little paperbacks each with different-colored sleeves. For years now, books from this series have been used bookstore treasures I buy automatically whenever I see them: volumes of Georg Trakl, Yves Bonnefoy, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Fidel Castro, Malcolm Lowry, Nazim Hikmet, Francis Ponge, and Charles Olson’s Mayan Letters in its first edition. (This last one was given to me by a friend as a birthday gift many years ago—nice friend!) The first volume in the series is The Scope of Anthropology by Claude Lévi-Strauss, which was the inaugural lecture at the Collège de France. Volume two in the series is Call Me Ishmael. Volumes three and four are two books by Roland Barthes, his first commissioned translations into English. (From where I sit, I can see the spine of the powder-blue jacket for Elements of Semiology, volume 4.) The fifth volume in the series is I Wanted to Write a Poem by William Carlos Williams. What else? Lichtenberg’s aphorisms. Karl von Frisch on bees. Zukofsky, Breton, Stifter, Neruda’s Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair, Han-shan, Baudelaire, and James Joyce’s Chamber Music. The run of these books is extraordinary. (There’s an unconfirmed rumor that these books might be reprinted and/or the series revived…)

The difference between having a culture or not is sometimes one person, in this case, one person publishing things, making them available in incredibly attractive editions. But let’s pause to take note that Tarn was doing this on the side, having already defined himself in a major way in a career as an anthropologist, while committing himself to the poetry he was writing (as well as famously translating). Both of those careers would be more than enough to merit serious attention paid either to Tarn the anthropologist or to Tarn the poet. The heroic, culture-defining work with Jonathan Cape, Cape Goliard, and Cape Editions would be the central fact in almost anyone’s literary life. In Tarn’s, it serves as a chapter, a Throw, one of many. (You can read about Cape Editions in Throw Sixteen, if you’re curious.)

The second portion from Atlantis that I want to draw your attention to is its forays into literary theory. Over the course of his long life in letters, Tarn has tended to distance himself from literary criticism, at least when characterizing his own work, though he has produced two books of essays in poetics and anthropology, Views from the Weaving Mountain (1991) and The Embattled Lyric (2007), both of which include criticism. (And neither of these volumes includes any of the many reviews he has written over the years. Tarn reads, he pays attention, and when moved to do so, writes about new books.) Nevertheless, Tarn’s approach to literature, when not explicitly anthropological, is nevertheless taxonomical. Like Goethe, Tarn’s imagination delights in categories and acts of classification. His eye is unusually sharp in this regard and his insights arrestingly helpful. Atlantis includes amid its pageant of vivid life details moments of reflection in which Tarn, like the Bateleur in the Marseille Tarot deck, seemingly lays his poet-magician’s wares on the table for all to see.

In Throw Thirteen, Tarn permits himself to put his work into perspective, considering and being daunted by the “totalizing” effect of the poetry he has written. “The body of work as held in the poet’s mind cannot, because it is open in only a limited way to prediction, be much more than the vision (or ‘prophecy’ if you like) of that total moment achieved by adepts at or before explosion” (123). (Explosion is such a provocative synonym—or perhaps better, metonym—for this total vision a poet has of their work.) Tarn views this experience of the total moment as fundamentally creative (even as it augurs destruction, cataclysm). Its antipode is “detotalization,” which he sees in a complementarity with totalization (and retotalization). “Detotalization,” he writes, is “the mental taking to pieces of such systems in ritual and liturgy for dialectical and didactic purposes, normally with retotalization in view. Thus begins all movement, all creation” (125). Totalizing allows Tarn to imagine Blake’s prophetic poems (something that delights Joseph Donahue in the brilliant Foreword he has written for Atlantis), specifically the meditation that in order for things to become total—in particular, at the end of a poet’s life—there must have been some dismemberment or disintegration beforehand, which the poet in some fundamental act of restoration seeks to repair. “In order for there to be an ecclesia,” by which Tarn means the mythical and religious systems that enable totalization over detotalization, “there must presumably have been a fall or breaking apart of the original unity: a sparagmos. Whether the process begins with a detotalization or a retotalization hardly matters: the process is in essence circular” (125). As an emblem of this energetic movement, this creation, Tarn envisions something surprising: heraldry. Well, it’s surprising in the literary critical sense—heraldry isn’t something literary critics think about. But it’s not surprising in the Tarnian sense, in that heraldry is a representation of a classifying imagination. “[A] strong heraldic order could endow a society with a powerful sense of security: a feudal system, carrying in its heraldry the element of classificatory thought, is a world where everybody can eventually be recognized over and above his or her individuality—contrasting with a modern world where, although everyone is recorded on computers, that record is a statistical one at best, involving not individuals but classes of individuals” (125). It takes the eye of a visionary poet-cum-anthropologist to show us that heraldry might restore us to our individuality. And an especially daring one to invoke a feudal system as providing a model for a sustaining creative collectivity.

Tarn is the greatest collector I have ever known. Like me, he’s a devoted birdwatcher. Atlantis begins with a note from May 13, 1972 about the spotty spring migration. Birdwatching is annual collecting. His personal library—including thousands of volumes housed in a custom-made concrete bunker—is legendary among poets who have visited it. Imagine essentially complete collections of books in every conceivable subject you are interested in, shelves and shelves of them, every book you could imagine and wish for. (The last of the photos in Atlantis shows the view from one of the corners of one of the bunkers in his house outside of Santa Fe.) For years, Tarn has been collecting stamps (no surprise), military badges and medals (especially Russian), airplanes and airplane paraphernalia, hats, and canes, to mention a few of the collections I’ve noticed over the years.

Heraldry is a way to emblematize collecting. Heraldic systems, writes Tarn, involve “a form of manageable simplicity that remains constant—the heraldic shield as a primary model—into which complexity is introduced by the manifold permutations that can be undergone by the content elements. My interest in and fascination with such diverse matters as heraldry itself—stamps, postcards, badges, medals, livery, uniforms, birds, islands, human bodies—revel in this constant interplay of simple form and complex content” (140). As an aside, the interplay between simplicity and complexity elegantly characterizes Tarn’s poetry. The heraldic system, for Tarn, involves a primal or archetypal form “that stands as the model for all possible forms.” What follows from that model is “grid-like classificatory projections” that creatively enable the archetype to be varied in successive heraldic iterations, from “that dawn-like shimmer of the lists that, in primitive and archaic poetry… have so fascinated poets and critics alike through the ages” to “the concept of metaphor…obviously involved” in contemporary poetics (141-2). These compellingly articulated thoughts, presented in the context of Atlantis as belonging to the mode of the ongoing and overall development of the literary persona Nathaniel Tarn, contribute so vividly to the texture and feel of this remarkable book, allowing us a look—a reflection on—the internal reality of a literary life, as important and involved as the many external realities so fabulously documented throughout Atlantis.

I won’t elaborate here anymore on heraldry. (Throw Fifteen is given over to this matter entirely; it’s also, notably, the subject of one of Tarn’s greatest works of literary study, “The Heraldic Vision: Some Cognitive Models for Comparative Aesthetics,” which appears in The Embattled Lyric.) But I want to note here, at the end of this encomium, that poetics is the living core of Tarn’s life in literature, in anthropology, in heraldry, and in collecting. I’ll repeat: What a life!

Peter O’Leary is the author of several books of poetry, including The Hidden Eyes of Things, a book-length poem about astrology and the unconscious, which will be published in the summer of 2022 by the Cultural Society. He teaches at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and, with John Tipton, edits Verge Books. He is also Nathaniel Tarn’s literary executor.